Since the early 2010s, social media has been identified with protesters. In the early days of platforms like Twitter, this was intuitive. Protest movements want attention, but mainstream media outlets were often slow or reluctant to give it to them, unless, of course, things got out of hand, at which point they’d get plenty. Social media, by contrast, was an effective tool for activists to organize and communicate with one another and directly with the public, providing counternarratives to the ones laid out in popular coverage. The opportunistic embrace of progressive causes by social-media executives cemented the perception: Twitter was with the activists.

Eventually, as more politicians, public figures, and members of the media congregated on social media, it also became a way for activists to command and guide elite attention, intervening directly in conversations from which they’d previously been excluded, nudging and sometimes forcing public discourse, increasingly enclosed within a few big platforms, in new directions. This sort of dynamic — social media used to organize protests that then produced encouraging imagery to further spread on social media — helped movements like Black Lives Matter spread across the country.

As most leftist activists would have told you at the time, this was always going to be a temporary arrangement. It contained clear dangers from the start; as much as Twitter and even Facebook leaned into their roles in “democratizing” the media, they were never truly building tools for activists, but rather surveillance networks for advertisers. And despite the social-media visibility of some left-wing movements, the ability to circumvent the media and to translate on-the-ground action into on-the-screen shareable content was valuable to activists across the political spectrum, including on the far right. (To whatever extent the term has meaning, January 6 was a social-media protest, too.)

Still, the events of this week — and the ways they’ve played out on social platforms — are a jarring reminder of how much, in a few short years, social media’s relationship with activism has changed. From the New York Times:

As protests in Los Angeles against the Trump administration stretched into their fifth day on Tuesday, social media creators have at times outnumbered the traditional press corps at rallies and have played an outsize role in sharing media about what has happened on the ground.

Outfitted with their own makeshift press helmets and vests, many creators — many of whom lean conservative — have livestreamed entire days of coverage and posted to social platforms like X and streaming sites like Twitch and YouTube. During some of the week’s most violent moments, Trump officials like Stephen Miller and billionaires like Elon Musk chose to amplify what the creators published, causing the posts to go viral and feeding the narrative that the violence has been out of control.

Contrast this with typical coverage from the Times in 2020, which described streamers as providing “lengthy alternatives to what some said were out-of-context video clips from mainstream news outlets” during racial protests. The paper declared a new era for progressive activism, inseparable from its medium:

Leveraging technology that was unavailable to earlier generations, the activists of today have a digital playbook. Often, it begins with an injustice captured on video and posted to social media. Demonstrations are hastily arranged, hashtags are created and before long, thousands have joined the cause.

At the core is an egalitarian spirit, a belief that everyone has a voice, and that everyone’s voice matters.

If you squint, you can make out versions of the same story — people bypassing the mainstream media to their own ends, the importance of social media in determining public perceptions of protest movements. There’s also an unmistakable tone shift from gently awestruck condescension to gently horrified condescension. (Disclosure: I was a reporter at the Times from 2016 to 2022, where I sometimes wrote about this subject.) In a far more significant sense, though, something is different. This week’s protests have been visible on social media, but their portrayals are fragmented, strange, and to people on the ground, often absurdly divorced from reality. If social media used to work for activists, or at least could, now it’s more effectively used against them.

This sort of narrative role-swap isn’t new. For all the attention Twitter got as a factor in the 2011 Egyptian revolution — a story embraced by the company’s leadership — the story of social media’s role in Egypt’s politics since has mostly been one of suppression, surveillance, and harassment. An American version of this story has been taking shape for a while. The most significant factor isn’t really about tech — it’s that the current administration is proudly hostile to protest and has cited social-media posts as thin pretexts for no-process arrests and deportations. An administration that both routinely threatens activists with imprisonment, deportation, or worse is more than enough reason for activists to regroup in spaces where privacy can be maintained, not just traded for attention.

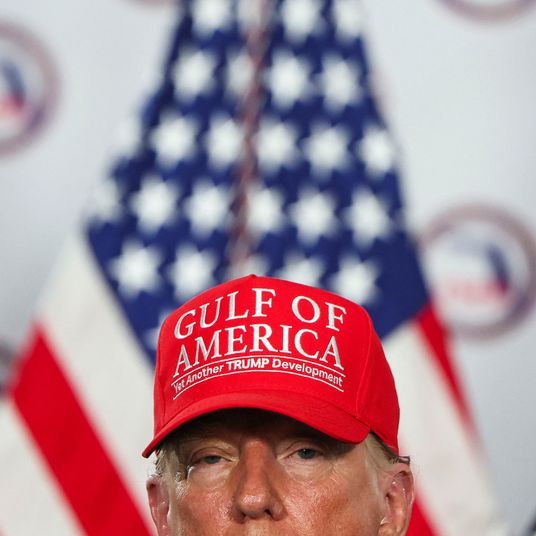

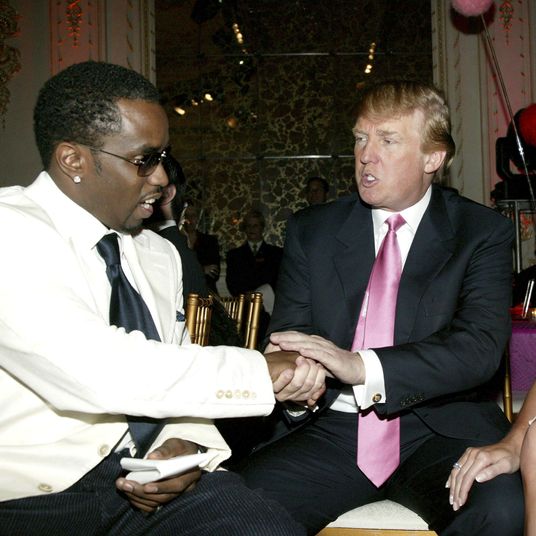

But social media really has been transformed, too, in ways both explicitly ideological and technical. Twitter, the platform people are most often referring to when they talk about these things, is owned by Elon Musk, who bought the platform with the explicit goal of disempowering its “woke” users and has more than accomplished his goal. Meta is still run by former BLM supporter Mark Zuckerberg, who more recently embraced Trump and pivoted to military contracting. TikTok, which is legally banned, is still online because the Trump administration promised not to enforce the law under vague and suggestive circumstances. Before its legal ban, TikTok’s rise set in motion industry trends that would alter social media’s relationship to activism in material ways. Meta, X, and Google reoriented their platforms around TikTok-style algorithmic video feeds, which relied less on users following one another and more on black-box per-user recommendations.

For the platforms, this meant more engagement. For activists, it meant there were no longer coherent public conversations in which to intervene, against which to push back, or to join in any meaningful sense at all. Platforms that were once useful for understanding and following the news became venues for pure spectacular consumption. In some ways this was novel and strange, with hundreds of millions of people consuming individualized feeds determined by automated recommendations. In other ways, it was familiar, since it was a reversion to pre-social-media power dynamics. The platforms were no longer social, in any meaningful sense of the word, but rather centralized and exercising constant (algorithmic) editorial discretion. At least as much as the mainstream media that’s now been twice replaced, TikTok-ified social media rewards decontextualized spectacle. This can be useful for activists to bring attention, generally, to their causes — at least some of the large swing in support for Palestinians can surely be credited to the endless stream of horrific videos from Gaza, which are plenty powerful without further context and don’t require the authority of a trusted follow. More often, though, the lack of a common chronological feed — the crude social-media proxy for a “shared reality,” I guess — produces disorientation, uncertainty, and the ability to retreat completely into ideological safety, pure fantasy, or both.

No reasonable progressive activist would have suggested, at any point, that these massive companies were genuine friends or allies. But now, the social networks — and the broader tech industry that has enabled more than a decade of American mass movements — are more clearly identified with, or even as, the enemy. This reality has been missing from a lot of the commentary on L.A. Much of it has tried to separate the viral images of burning Waymos, which have dominated coverage from both mainstream media and right-wing influencers, from the protesters’ broader response to ICE raids and the threat of more federal troops. Brian Merchant, reporting from the ground, offers a slight corrective:

Google suspended Waymo service to downtown LA, and also in San Francisco, where solidarity protests unfolded. “Why the self-driving cars were targeted remains unknown” is a refrain I heard multiple times on TV and radio news. The reason does not seem so secret to a lot of people.

“Oh they called them up on purpose, lit ’em on fire like that,” a cameraman shooting on the scene the next day told me. The charred husks in a neat line do seem to suggest that was the case. Other witnesses and journalists who were there shared the same story: People summoned the cars to light them on fire when they arrived. Protestors were reportedly calling them “spy cars” as they were vandalized and set ablaze, and some noted how the cars can share data with the LAPD.

The temptation to sift this out as the work of rogue anarchists or shit-stirring hangers-on is understandable and probably largely true. But the targets of destruction aren’t always random, and it’s worth thinking about what they mean. The stakes and risks of such a protest in June 2025 are high. If a protester is already worried their own phone could get them arrested and prosecuted, taking now-standard precautions to lock it down and disconnect it while being careful not to take photos with identifiable faces in them, how might she see a driverless car covered in cameras and owned by Google?

Where do things go from here? In her User Mag newsletter, Taylor Lorenz suggests that progressive disengagement from — and the right’s massive, well-funded right-wing investment in — the influencer culture of algorithmic social media has left the platforms to Trump and his allies, but also suggests a queasy way out: “people with resources” stepping in to finance an alternative. Pro-Trump (or at least anti-protest) voices do seem to be dominating, although one consequence of a post-feed platform is that it’s harder to tell. At the very least, platforms like Instagram, TikTok, and even X have remained somewhat useful for sharing raw — and particularly shocking or exonerating — footage of physical altercations.

Meanwhile, the dozens of groups organizing under the banner of this weekend’s “No Kings” protest, scheduled to counterprogram Trump’s military parade, are trying to figure out what large-scale protest organization looks like in 2025. (Partners include federal employee unions and faith-based groups.) They’ve been able to get media coverage, and word has spread in Instagram Stories and TikTok posts. (Despite the open planning and explicitly nonviolent language of its organizers, the protests have already earned a National Guard deployment in Texas.) They, too, acknowledge that something has changed. On its “Social” page, No Kings supplies suggested messages to supporters and invites them to share on BlueSky.

More From This Series

- Mark Zuckerberg Is Convinced He Can Buy the Future

- Are You Ready to Watch TikTok on TV?

- At Work, at School, and Online, It’s Now AI Versus AI