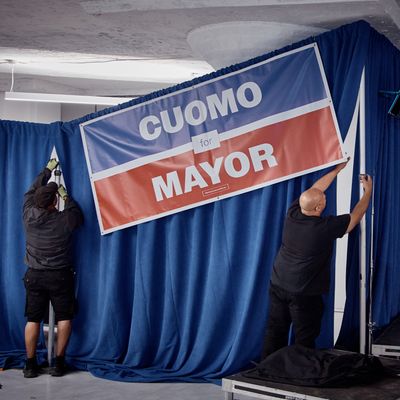

One of the reasons Zohran Mamdani’s smashing victory yesterday created such a sensation is that public polls (overall) did a poor job of predicting the size and shape of both his and Andrew Cuomo’s coalitions in the Democratic mayoral primary. An average of these polls prepared by Race to the WH showed Cuomo with 36.4 percent of first-choice ballots and Mamdani with 28.6 percent. While nearly all of these polls showed Cuomo being pushed into a ranked-choice battle with Mamdani, and a few (notably the final survey from Emerson College) showed the democratic socialist prevailing in the final calculation, only one public survey, from Public Policy Polling, predicted a first-choice Mamdani plurality. No one provided evidence of a Mamdani plurality so large that his nomination was certain without waiting for the final ranked-choice numbers.

The polling miss will be a source of great joy among a certain segment of the public and the punditry that thinks polling plays too great a role in contemporary politics — or that would like to get rid of polling altogether. The idea that we should rely on hunches, spin, prejudice, and tiny-sample reporting to get a handle on public opinion rather than trying to measure it objectively strikes me as, to use a technical term, willfully stupid. But partly to rebut polling nihilists, and to promote a better understanding of what polls can and cannot be expected to do, it’s worth a look at why they were wrong in New York. Here, a few reasons:

Polls are snapshots of fast-moving races

This explanation may seem too obvious to require explanation, but highly dynamic multicandidate contests often take shape late in a cycle, when ads and get-out-the-vote efforts have reached their maximum impact in both persuading and mobilizing voters. Polls often can’t capture such trends, which is why we often mystify them with terms like momentum. Only a few pollsters (e.g., Marist, Data for Progress, and Emerson) did multiple surveys, making apples-to-apples comparisons possible. There was clearly a Mamdani trend underway, but its size and durability was hard to nail down.

Primary polling is always shaky

It’s a truism in the political-analysis biz that polling for general elections is typically more accurate than polling for party primaries. The reasons are simple enough: Much of the electoral behavior we see each November is entirely predictable thanks to partisan patterns that recur time and time again and change slowly, if at all. Candidate choice in primaries is far less mechanical and thus is more fluid and harder to capture. So fairly sizable polling errors in primaries are actually normal, not a sign that they are for some reason becoming useless or misleading. You should just add a few grains of salt to any primary poll.

Turnout in a race like New York’s is extremely hard to predict

All polls are based on models that make certain assumptions about the shape of the electorate, which in turn depends on turnout patterns. There’s nothing much more difficult to predict than who will show up for a municipal primary in late June of a non-presidential, non-midterm election year. For all the local and national hype, heavy campaign spending, and genuine excitement associated with the New York mayoral primary, turnout was only about 30 percent. The value of precedents was limited; for one thing, the advent of early-voting opportunities (a relative novelty in New York, where there was no early voting prior to 2019) has added a new variable to turnout and likely helped boost the participation of the younger voters who backed Mamdani so decisively. More fortuitously, the extremely high temperatures that afflicted the city on Tuesday likely depressed turnout among the older voters central to Cuomo’s prospects for victory.

Ranked-choice voting complicates everything

This was only the second mayoral primary conducted under the controversial ranked-choice voting system, which allows voters to express second-through-fifth-place candidate preferences, with a postelection calculation eliminating lower preferences until someone wins a majority. While there has been a lot of talk about how RCV might affect who won or lost, it’s equally important to comprehend that the system has a complex and hard-to-measure impact on campaign strategies (especially the cross endorsements that Mamdani used effectively) and how voters process their own decisions, particularly when everyone is still a novice at utilizing RCV. A lot of late-deciding voters were just figuring out how RCV worked, which very likely affected how they responded to polls.

Maybe 2025 is a bad year for pollsters

It’s almost always a bad idea to generalize from any one contest, or any one election cycle, that “the polls” (another generalization) are good or bad. For one thing, they are always useful in providing analytical data, even if they’re “wrong” about predicting winners or winning margins. Some data is better than no data at all. Beyond that core dogma, which cannot be repeated too often, the reality is that polls are more accurate in some election years than others and vary by the type of race involved. Most famously, the 2016 presidential-general-election polls were pretty accurate at the national level but erred decisively in the battleground states that unexpectedly vaulted Donald Trump to the White House. Similarly, 2024 general-election polls were reasonably accurate, but a slight underestimation of Trump’s vote in the battleground states, which tilted all of them into his column, made them seem off. 2020, by contrast, was a “bad” presidential election for polls, in part because the pandemic introduced a lot of uncertainty into turnout patterns and candidate preference alike.

Polling in non-presidential election years is harder to assess because they are less frequent and consistent, and the only “national” numbers predict the overall House popular vote, which is not that tightly related to the number of seats won or lost. But 2022, to cite the most recent example, was a “good” midterm election for polls. There’s no telling what the scattered election landscape of 2025 will ultimately show (there’s no public polling at all in many off-year races), and pollsters are constantly refining their methodologies as well. So the smart thing to do is to wait a beat, or two, or three before making any sweeping judgments about what the New York City results mean for the relevance of polls.

More on the Zohran Mamdani victory

- Bill Ackman Dumps Cuomo, Embraces Adams

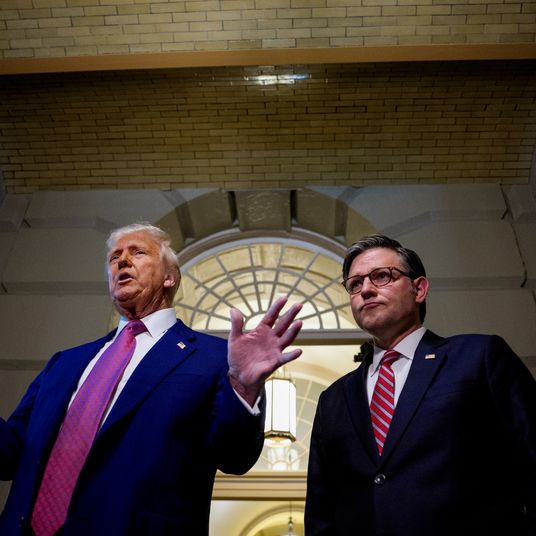

- Trump Ramps Up Threats to Arrest Mamdani

- Can Zohran Mamdani Buy the NYPD’s Support?